Because of their numerous and much publicized exploits during the Second World War, the United States Navy's motor torpedo boats--the PT or 'mosquito' boat--have long caught the imagination of thousands of Americans. A total of 808 of the craft were contracted for by the Navy during the war; 525 of these speedy little torpedo-carriers were actually built, including those Lend-Leased to the navies of Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Far too small and built in too many numbers to be awarded names (except by those that manned and fought on them), two boats have still managed to become known to historians and the general public alike. PT 41 was a unit of the six-boat Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Three based in the Philippines at the outbreak of war with Japan in December 1941. The squadron is best known to most Americans of the World War II period as the PT unit that spirited General Douglas MacArthur, his family, and his staff from the Philippine fortress of Corregidor in March 1942. Commanding the squadron was a dedicated and pugnacious Navy lieutenant named John D. Bulkeley, and it was aboard his PT 41 the General and his family rode during the trip to Mindanao in the southern Philippines, where US Army Air Force bombers carried them to Australia. The feat earned the scrappy Bulkeley the Medal of Honor, while every other officer and man in the squadron who participated in the mission was awarded the Silver Star. Both the boat and the squadron (not to mention Lieutenant Bulkeley) were made famous by the publication in late 1942 of the book 'They Were Expendable', which detailed and romanticized MTB Squadron Three's operations between December 1941 and the squadron's destruction in April 1942. The best-selling book was later made into a film released in December 1945 starring Robert Montgomery (himself a former PT officer) and John Wayne. The movie has been a staple for late night television and classic movie cable channels for years, and has recently been made available on video and DVD.

|

|

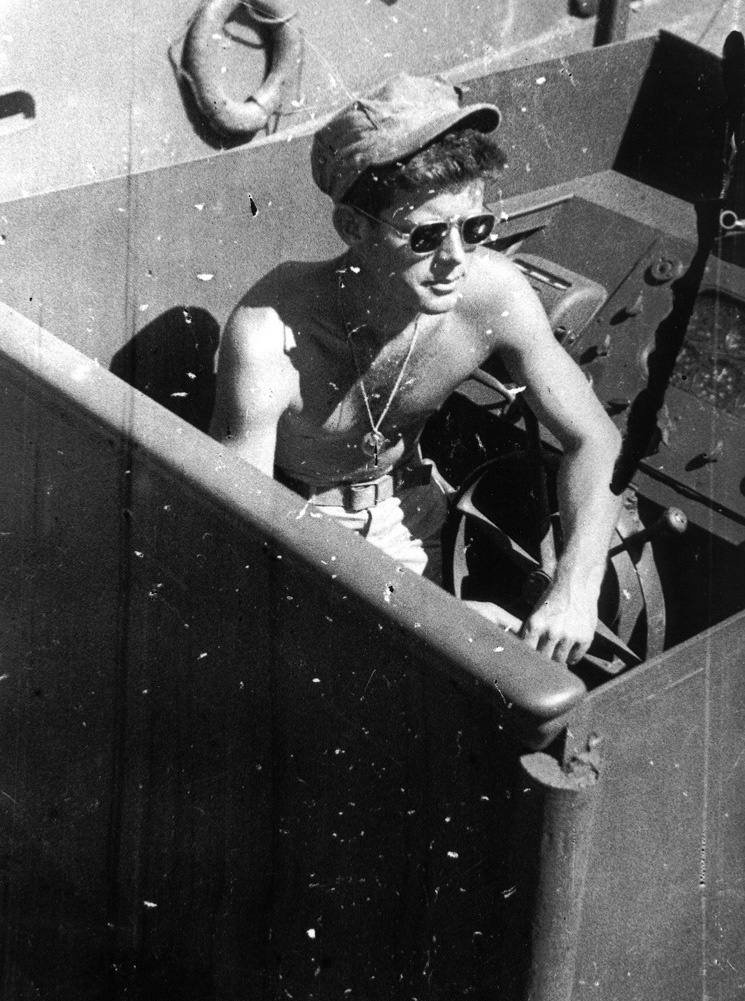

(l) Lt. John D. Bulkeley USN. (r) Lt. j/g John F. Kennedy USNR.

(PT Boats, Inc., John F. Kennedy Library)

On the other hand, PT 109's fame comes from the fact that her last skipper--one John Fitzgerald Kennedy--would later be elected thirty-fifth President of the United States. Because of books, numerous magazine articles, a film, and several documentaries, most adults of a certain generation are at least slightly familiar with the basic story of PT 109's end. Rammed by a Japanese destroyer, trapped behind enemy lines and all but given up for dead by their shipmates, Kennedy and his crew were ultimately rescued after a week by friendly Melanesians and an Australian coastwatcher. The discovery of the boat's remains in May 2002 focused even more attention onto what was admittedly a minor event in the course of the war. Due to Mr. Kennedy's election as President in 1961 much has been mentioned about the late president's Navy service, either good, bad, or irrelevant, leaving many to mistakenly conclude that JFK's naval career and the boat's service life began and ended together. But what most people are unaware of is that the 109 had a combat history long before John Kennedy ever knew of the boat's existence. Much has been written of this particular PT's famous final skipper, but what was the 109's story before the man from Massachusetts first trod upon her deck? Delivered to the Navy in July 1942, PT 109 would see considerable action off the shores of an island in the Pacific, the battle for which has all but become legendary in a war branded by great battles: Guadalcanal. Before then-Lieutenant (junior grade) Kennedy took command of the 109 in April of 1943, the boat was just another of the many small fighting craft sent to the South Pacific to intercept and harass the 'Reinforcement Unit' of the Nihon Kaigun--the Imperial Japanese Navy--that operated an almost-nightly delivery service of food, men, and supplies to their Army garrisons entrenched on the island.

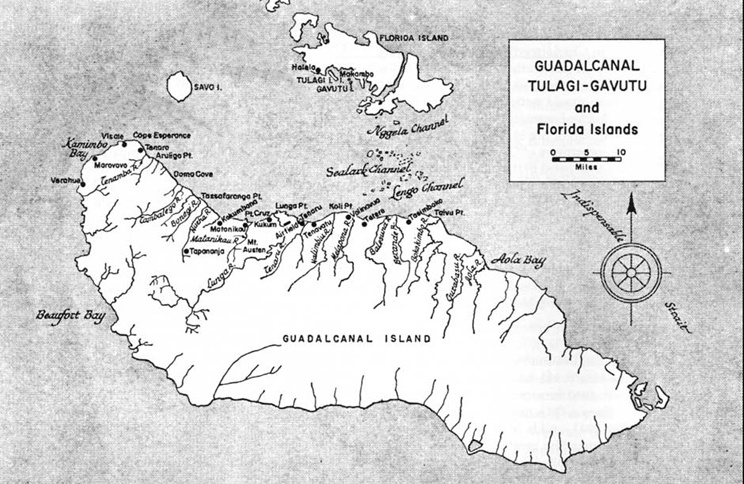

On August 7, 1942 the United States Marine Corps' First Division landed on Guadalcanal and the nearby islands of Florida, Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo, initiating the first offensive action by United States forces in the Pacific War. Although stunned and surprised, the Japanese were determined to drive the Americans out of their newly established toehold, and would quite soon made their intentions dramatically and painfully clear. In the early morning hours of August 9, a Japanese cruiser force attacked a similar Allied unit guarding Marine transports anchored off the Guadalcanal beachhead. The Japanese sailors, well-trained in night-fighting, caught the Allied ships unprepared and were victorious in little over twenty minutes--leaving US cruisers Astoria, Quincy, Vincennes, and the Australian cruiser Canberra to permanently rest and rust at the floor of what would soon become known as 'Ironbottom Sound'. In the aftermath of what would later be called the Battle of Savo Island the tone was quickly set for the fighting to come, both on land and at sea--a six-month siege that would see both sides sacrifice many men, planes, and ships for possession of the island; a ninety-mile long strategically-placed strip of dirt crowned with foul, stinking, disease-ridden and insect-infested jungle.

United States Marines landing on Guadalcanal, August 1942.

During August the Japanese would make many air attacks on Guadalcanal, and several times landed troop reinforcements in an attempt to push the dug-in Marines off the island. In September and October Emperor Hirohito's sailors increased their efforts, using their cruisers and destroyers to make small nighttime landings. Because of both the tremendous losses at Pearl Harbor and the demands of fighting a two-ocean war, the US Navy suffered from a grevious lack of capital ships, and simply did not have the resources to counter all of the Imperial Navy's nocturnal incursions. Even prior to December 1941 American shipyards were desperately going hammer-and-tongs around the clock turning out the warships and auxiliaries so desperately needed by the Navy, but it would be many months before new ships with trained crews would arrive in the combat zone.

Guadalcanal, Florida, and Tulagi.

As the battle on land degenerated into a bloody slugging match, the fighting at sea began to take a peculiar pattern of its own. Thanks to the presence of American aircraft based at Henderson Field on the island, control of the waters around the island underwent a regular 'shift change' every twelve hours. 'Day shift' was the dominion of the Americans; US warships and transports operated quite openly in the sea around Guadalcanal and Tulagi without fear of interference from Japanese surface ships, all the while keeping one wary eye skyward in case Japanese air elements elected to put in their almost-daily appearance. The Imperial Navy knew better than to run warships in daylight around the islands while it seemed even the birds wore American air force insignia. The few times the Japanese sailors felt bold enough to attempt a daylight sortie, their ships became lunchmeat for the 'Cactus Air Force' of Marine, Navy, and Army Air Force planes based at Henderson. But as the day faded and the dusk approached, all ships of the Stars and Stripes energetically hoisted anchor and hurried out of the area, to borrow a phrase from historian Samuel Eliot Morison, 'like frightened children running home from a graveyard.'

The arrival of Japanese warships--the Tokyo Express--heralded the 'night shift'. Originating from bases at Rabaul in New Britain, and from Bougainville and the Shortlands in the northern Solomons, the Express (so-called because their nocturnal deliveries were made with express-train regularity) sailed under their banner of the Rising Sun unchallenged into Ironbottom Sound. These ships of the Imperial Navy had their decks loaded with food, men to reinforce the numbers of Japanese troops ashore, and weapons and ammunition with which to diminish the number of their Marine enemies. The samurai seamen also brought something along for the American defenders, as well--once the Japanese ships withdrew from the landing areas and cruised past the Marine-occupied sector of the island, the Imperial sailors pointed the muzzles of their heavy guns toward the American positions and treated the bone-weary Leathernecks and their much-prized airfield to a sleep-destroying, plane-wrecking bombardment. But the sailors of the Rising Sun didn't stay around in Ironbottom Sound too long to exult in their disruption of American shut-eye, or to greet their flag's heavenly namesake, either. First light usually found the Imperials steaming up the New Georgia Sound--nicknamed 'The Slot'--as fast as their ships' boilers would allow, and well out of range from any prowling American aircraft from Henderson that survived the previous night's shelling. Any attempt by either side to change this constant and wholly undesirable state of affairs usually resulted in a major naval confrontation, and the ensuing clash promised to be phenomenally violent. The end result of such an engagement for the Americans would be the pitifully few US warships nursing wounds in rear area bases. For the Japanese--with more vessels readily at hand--it was back to business as usual resupplying their men ashore and making the Marines' existence more miserable.

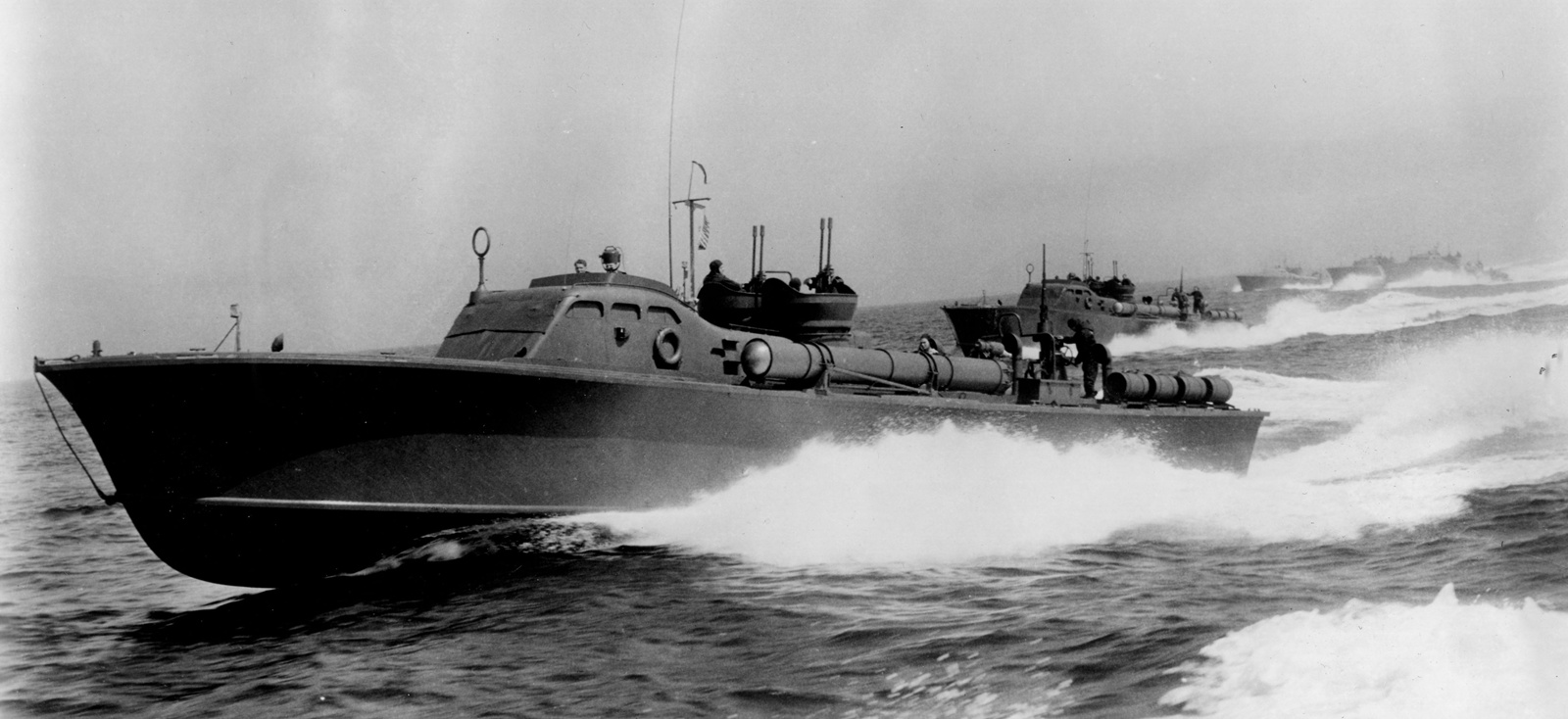

The mission of the PT boats, conceived as it was 'in a mood of desperate optimism', was to prevent both the reinforcement runs and the bombardments by the Tokyo Express when US Navy big guns were unavailable. For four miserable months--from October 14, 1942 to February 1, 1943--the officers and men of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons Two, Three, and Six ventured out into Ironbottom Sound night after night, putting their boats and their lives on the line to stop the Japanese. As flagship of MTB Squadron Two, PT 109 participated in twenty-two patrols, coming in contact with the enemy six times between November 1942 and February 1943. These encounters consisted of torpedo attacks on enemy ships, strafing enemy shore positions, shootouts with cargo-carrying barges, dodging night-flying floatplanes that would bomb and strafe the PT boats as they attempted attacks on Japanese destroyers, and the destruction of supplies dropped off by the Express. In addition, other jobs the boat and her crew performed were searching for downed pilots, pulling sister boats off of the treacherous, unmarked reefs that surrounded the islands, and picking up not only survivors of the intense PT-versus-destroyer duels of the campaign, but also those sailors of ships sunk during the mighty big-ship battles waged between Japanese and US task forces.

In December 1941--shortly after America's entry into World War II--the Electric Boat Company was awarded a contract to build thirty-six PT's of their newly-designed PT 103-196 series; these were the craft whose sillouette would define the term "PT boat"--and it is from this series the story of the craft destined to become the most famous PT boat of World War II (due in no small part to the subsequent employment of her last skipper) was to begin. Along with New Orleans' Higgins Industries and the Jacksonville-based Huckins Yacht Company, Electric Boat was one of the main builders of motor torpedo boats for the US Navy. The seventh boat of that series first took shape on March 4, 1942 with the laying of 109's keel, and the boat first took to the water three months later on June 20th. The 103-series PT's were the successors to Elco's pre-war craft, the PT 20-68 series seventy-seven foot boats; the 103's were an entirely new design, built to capitalize on the strengths of the 77-foot model, while attempting to overcome some of its drawbacks. Eighty feet long, with a twenty foot beam and weighing in at 50 tons fully loaded, the new boats were a knot or two slower than their predecessors, and also slightly less manuverable. But the 103's rode more comfortably than the 77-footers, which had a tendency to pound heavily while underway at sea. The 80-footers' slightly larger size and more robust construction also allowed the boat to carry more and more guns as the war progressed.

(Above) PT 117, an Elco 80-footer, running trials, August 1942. (Below) A division of Elco 77-footers at speed. (National Archives, Author's Collection)

Like the earlier Elco PT's, the new boats were constructed from many materials: the hull was initially constructed upside down with frames made from laminated spruce, white oak, and mahogany, the keel made from spruce and oak, and the whole assembly double planked with one-by-six-inch mahogany boards. Sandwiched between the two layers of planking was aircraft canvas liberally soaked in marine glue, enabling the hull to maintain its strength and watertight integrity. After the hull was completed, it was turned over to begin assembly of the deck, which (in the early days) was double-planked in a similar manner as the hull. Frames of spruce, covered with plywood sheets formed the cabins.

80-foot Elcos on the assembly line, early 1942. (PT Boats, Inc.)

Providing the boat's motive power were three Packard V-12 4M-2500 engines; initially rated for 1,200 horsepower, later variants rose in performance to 1,350 and finally 1,500 horsepower as the boats gained weight from more and more weapons and equipment. Powerful and reliable, the Packards were especially adopted for PT use, and consumed three thousand gallons of 100-octane aviation grade fuel. With engines in tune and with a clean bottom, the three Packards could push a fully-fueled, fully armed PT across the water at a maximum speed of forty-two knots. And when silence for a sneak attack was desired, mufflers attached to the exhaust ports at the stern enabled the boats to silently creep along at about ten knots.

The Packard V-12 4M-2500 engine. (PT Boats, Inc.)

Armament included four .50 caliber Browning M-1 machine guns installed in two manually-operated twin turrets--one was mounted forward and to starboard of the cockpit, the other was aft and installed on the port side of the dayroom canopy. This layout gave the guns a better field of fire than the side-by-side arrangement of the unreliable hydraulic gun turrets mounted on some of the early Elco-77's; also, both pairs of guns to be brought to bear on a target coming from broadside. A 20mm Oerlikon Mark IV automatic cannon was mounted on the stern for anti-aircraft defense, while four 21-inch Mark VIII destroyer torpedoes launched from Mark XVIII tubes utilizing a black powder launching charge completed the factory installed armament fit. Unfortunately for the PT sailors, not until they were in the heat of combat would they realize their primary weapon was literally an embarrassing dud. An obsolescent relic from the First World War, the Mark VIII was plagued by many vices, chief of which was its slow speed (27 knots), a small warhead containing 300 pounds of TNT, a tendency to run wild especially when set for shallow depth, and a defective exploder that would detonate prematurely, if it bothered to explode at all. It was later estimated sixty-three percent of the Mark VIII torpedoes in service had deficienies in either their depth-setting mechanisms or in the exploder.

Another problem was the method of launching the weapon; in combat the powder charge occasionally misfired, causing the torpedo's fins to strike the deck of the PT as it left the tube, making the weapon run erratically as it entered the water, and missing the intended target. An even greater hazard was the "hot run"--where the torpedo would remain in the tube with the torpedo motor running wildly and kicking up a tremendous racket. In these situations there were only a few hair-raising seconds for the torpedoman to shut the motor down before it disintegrated and exploded, sending shrapnel-like fragments of torpedo and tube sailing across the deck.

Torpedoes were also covered with a heavy coating of grease and oil prior to installation in the tubes, in order to assure the weapon's smooth ejection. But the powder charge occasionally had the disconcerting habit of igniting the oil as the torpedo left the tube, causing a brilliant red flash. This naturally revealed the boat's position to the enemy, enabling the target to maneuver out of the way of the PT's torpedoes, while in turn making the boat an excellent target for retaliatory gunfire. Maximum range of the Mark VIII was 10,000 yards, but this was excessive because the boats' torpedo fire control apparatus was not accurate enough to permit such a long-range shot. In actual practice the PT's usually crept to within 1000 to 100 yards of their intended victim with engines muffled before letting loose with a torpedo spread. In contrast, the Japanese Type 93 destroyer torpedo (the infamous 'Long Lance') was 24 inches in diameter, possessed a massive warhead in which was packed 1,080 pounds of high explosive, a top speed of 45 knots, and a range of up to 40,000 yards.

Later in the field 300 pound Mark VI depth charges were added for possible anti-submarine work, but since the PT's did not possess any sort of underwater detection equipmment, the best the boats could do was harass (if not destroy) enemy submarines. Depth charges later found a use in destroying barges that were built too tough to be sunk by PT gunfire, or discouraging the pursuit of any Japanese destroyer that came too close to a fleeing PT. The depth charge's three hundred pounds of TNT was just enough to break the back of any enemy destroyer if it went off at the right moment. Additional weapons and equipment were the crew's small arms--Colt .45 automatic pistols, a Thompson .45 submachine gun, Springfield rifles, a riot gun, the occasional hand grenade, and a 35 gallon non-refillable smoke generator on the stern. The crew complement normally numbered two officers and nine bluejackets: the boat captain, the executive officer, the radioman, a quartermaster, the gunner's mate, the machinist's mate, two firemen, a torpedoman, the ship's cook, and a seaman.

After several days of exhaustive trial runs, the Electric Boat Company transferred custody of PT 109 to the United States Navy on July 10, 1942. A newly-minted graduate of the Navy's new Motor Torpedo Boat Training Center named Ensign Jack J. Kempner and a temporary crew of five sailors came aboard and unceremoniously took posession of the new boat. After a brief inventory of equipment, the engines were started and Kempner eased the factory-fresh PT from the the busy docks of the Elco boatworks, threading the new boat through Newark Bay and into the channel of water known as the Kill van Kull. After passing underneath the Bayonne Bridge and guiding 109 through the narrow passage of the Kull, Kempner pushed up his throttles as 109 entered the wider water of New York Bay, increasing the boat's speed as 109 roared past Ellis island and the Statue of Liberty standing off the boat's port side. From New York Bay, Kempner steered 109 into the East River, below the bridges of Brooklyn and Manhattan, finally entering what would be PT 109's first base of operations--the New York Navy Yard. Upon her arrival the boat tied up to the YR-28, a former barge converted into a floating workshop, and joined her six sister boats--PT's 103 to 108--in service with Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Five, commissioned on June 16 as the first squadron to be equipped with the new Elco eighty-footers. The squadron's other five boats, PT's 110 to 114--would join them in the weeks to come.

Later that afternoon, Seaman 1/c Adam S. Sennick arrived with his orders assigning him permanent duty aboard 109. The temporary crew left the boat on July 18, and the of the rest of the permanent crew--one officer and eight men--arrived to take their places; Ens. Bryant L. "Bud" Larson, Quartermaster's Mate 2/c James Guy Manning, Motor Machinist's Mate 2/c Clayton A. Craig, Ship's Cook 2/c Joseph J. Morrissey, Torpedoman's Mate 2/c Jack Edgar, Radioman's Mate 3/c Edward R. Guenther, Fireman 2/c Lawrence R. Wallace, Seaman 2/c James R. Marney, and Fireman 3/c Joseph F. Hubler. Because he had been one class behind Kempner at the Training Center, Ensign Larson became the boat's executive officer.

Some of PT 109's first crew. (l/r): Ens. John J. Kempner USNR, Ens. Bryant L. Larson USNR, Edward R. Guenther RM3/c USNR, and Clayton A. Craig, MoMM2/c USN.

(PT Boats, Inc.)

At this time, the commander of Squadron Five was Lt. Cmdr. Henry Farrow. Like many of the PT squadron commanders in those early days, Farrow was a career Navy man. PT personnel were normally drawn from reservist volunteers, but in order to have a cadre of career Navy people in the program, a few Regular Navy officers and men were simply assigned to the first squadrons. Farrow was a quiet, reserved officer; old-school Navy to the core, he apparently did not care much for his assignment to motor torpedo boats. It has been written that he rarely rode his squadron's boats (never even learned how to operate a PT), and ran Squadron Five as if he were the captain of a battleship, with a certain aloofness towards his junior officers, and was rather content to let the squadron exec, Lt. Henry Montgomery (a movie actor before the war best known by his stage name, Robert Montgomery) handle the day-to-day running of the unit. But Farrow was a competent naval officer, and in his own way managed to school the young reserve officers of his squadron in the ways of the Navy.

Lt. Cmdr. Henry Farrow USN, Squadron Five CO

As Farrow tasked himself with organizing the twelve boats of Squadron Five into a cohesive whole, Ensign Kempner and his crew did their own part by putting 109 through her paces during the boat's shakedown trials, working out any bugs in their new craft; while each man of the crew went about the business of learning his shipboard duties. The boat ran cruises in Long Island Sound and participated with the other boats in squadron formation exercises in open Altantic waters; Ocasionally, longer trips were made from the Navy Yard to Archie Fyfe's shipyard at Glenwood Landing, New York (where intallation of some equipment was done) or the Training Center at Melville. Once the day ended, the PT's returned to the Navy Yard and the YR 28, which serviced the boats as sort of a PT tender. Most everyone felt they had a good boat--it performed well enough, but Ensign Larson held the view that 109 didn't seem as as fast as the other PT's in the same class. All the same, the brand-new boat was well built, powerful, seaworthy, and maneuverable.