|

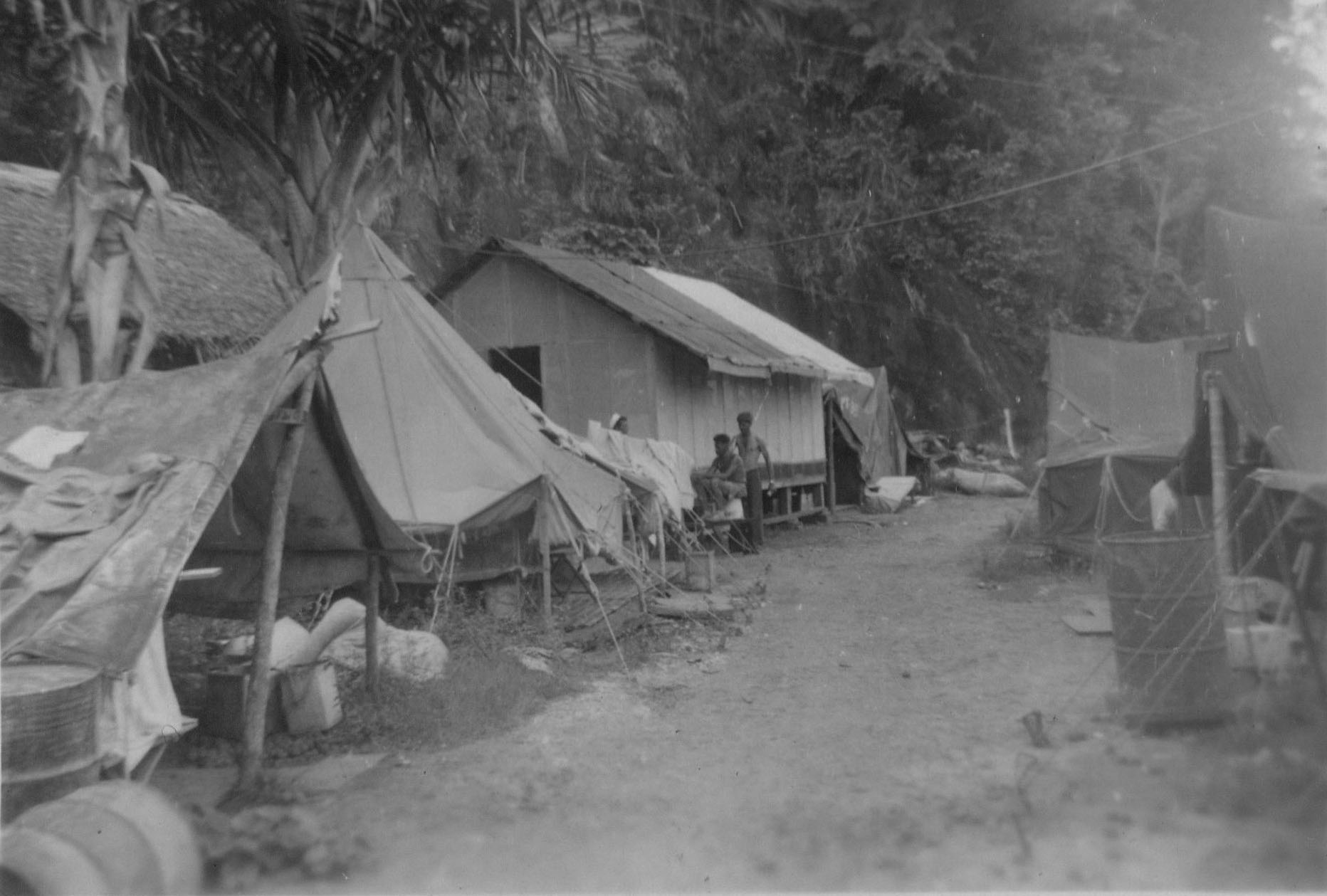

The living quarters at Tulagi, 1942-43. (PT Boats, Inc.)

Chapter Four: Sunk at Sea

A major problem faced by both sides fighting in the tropics was the constant battle to stay healthy in the face of the many local diseases transmitted both by germ and insect. On January 8 quartermaster Guy Manning reported to the hospital with tropical fever. Malaria, dengue fever, and dysentery run rampant in the Solomons, and disease had taken its toll of a number of boat and base personnel, especially those who were the first to arrive in October 1942. A machinist's mate in Squadron Three died from peritonitis in December; several other officers and men were so ill they were transferred to shore duty, while extreme cases were sent back to the States for recovery. This created a major manpower problem among the squadrons, since replacements were slow in coming, and crews were broken up in order to keep the PT's manned for nightly patrols. A pitiful few came from Melville, some were transferred form other base commands, still others came from the crews of ships lost in earlier battles. To deal with the tropical maladies, drugs such as atrabine were available, but it had such a foul taste that it caused some men to vomit. If that weren't serious enough, most of the men were reluctant to take the drug because of then current but untrue rumors that atrabine caused a man's skin to turn permanently yellow, as well as rendering one impotent. An additional hazard was reserved for the motormacs--sitting in the PT's hot, poorly ventilated engine room, shifting gears on orders from the cockpit and doing what was necessary to make sure the engines performed flawlessly when the situation demanded it, exhaust fumes crept back into the engine room when the boats ran muffled down. It was later found that the muffler installations on a number of the older boats were defective, and the fumes leaking back into the engine room put the engineers into a carbon monoxide stupor.

The make-up and cargo composition of the next run of the Tokyo Express, slated for the night of January 10-11, was influenced by several factors; mechanical troubles in the Japanese destroyer force, a bombardment of Munda airfield by Allied naval forces the night of January 4-5, and search plane reports on the 7th and 8th. Rear Admiral Koyanagi led the night's eight-ship Express run, with four destroyers-Arashi, Arashio, Oshio, and Makinami--carrying cargo, while Kawakaze, Kuroshio, Hatsukaze, and Tokitsukaze provided cover. A coastwatcher up the line sent a report the Express was on the way, but the message came too late for Henderson's planes to make an intercept; the same report reached Tulagi PT headquarters while four PT's were already on patrol, keeping watch along the Savo-Cape Esperance line: PT 45 (Lt. Lester Gamble), and PT 39 (Lt. j/g Ralph O. Amdsen, Jr.) patrolling to the west, and PT 48 (Lt. Robert Searles) and PT 115 (Ens. Bartholomew J. Connolly III) on the eastern side of the line. Lieutenant Westholm mustered his crew of PT 109 for action, and quickly ordered five other boats to get underway: PT 43 (Lt. Charles Tilden), PT 40 (Lt. Clark Faulkner), PT 36 (Lt. j/g Marvin Pettit), PT 46 (Lt. Henry Taylor), and PT 59 (Lt. John Searles). As Westholm climbed aboard 109, he was dismayed to learn that the engines would not start; the crew hastily disembarked their boat, commandeered Ens. George S. Wright's PT 112, and went roaring off into the night. Westholm, Tilden, and Faulkner were to patrol an area between Cape Esperance and Aruligo, while Searles, Taylor, and Pettit were to guard an area further east, near Tassafaronga and Doma. As Westholm sailed PT 112 towards the patrol area, Torpedoman's Mate Claude Dollar came to the bridge and handed exec "Bud" Larson a "lucky bean", given to him by one of the natives. Dollar asked Larson to hold on to it, as he felt that the crew may need some special luck that night--little did the superstitious torpedoman know how right he would be.

Koyanagi's ships came in under cover of a rain squall, which while brief, allowed the Express to slip undetected past the two scouting sections at the Savo-Esperance line. As the transport unit busied itself heaving overboard drums unmolested, a portion of the escort section was spotted a half-hour after midnight by Westholm's division. The Squadron Two leader, along with Tilden and Faulkner, were on a northwesterly heading a quarter-mile from the Guadalcanal shore, while the Japanese destroyers were in column formation one mile further out, moving slowly in the opposite direction. The set-up was perfect--the Japanese destroyers were to seaward, silhouetted by the starlit sky, while the American PT's were hidden in the inky blackness of the Guadalcanal landmass. Westholm was just about to pass the word to fire torpedoes when a Catalina pilot, aloft and scouting for the PT's, broke into the radio circuit demanding to know, "What's going on down there? What's happening??" After a few tense moments, Westholm gave Faulkner and Tilden the word to attack; "Deploy to the right and make 'em good".

With Westholm at the firing buttons, Larson guided PT 112 to about 400 yards from the third destroyer in the column; PT's 43 and 40 also lined up on their targets. Aboard the 112, Westholm fired all four tubes; the other two boats let go with their torpedoes about the same time. A flash from one of PT 43's tubes as her torpedoes entered the sea alerted the Japanese sailors to the hitherto unknown presence of the torpedo boats, and the response was predictable and immediate. A volley of 5-inch shells screamed in the direction of the PT formation, seeking the boats' vulnerable 100 octane gasoline tanks. Larson pushed the throttles up, bringing the engines of the 112 to full speed, and began cranking the helm hard left in an attempt to run astern of his target.

While the PT's busied themselves hunting for the nearest exit, a damaging but not fatal torpedo hole suddenly materialized underneath the wardroom of destroyer Hatsukaze, from either PT 112 or PT 40. Initially the ship's captain thought his ship was finished; although the blast killed eight sailors and wounded twenty-three others, the destroyer was able to make it back up The Slot at sixteen knots under escort from two of her sisters, illustrating the inability of a single Mark VIII warhead to inflict major ship-killing destruction. Destroyer Tokitsukaze evaded the two torpedoes fired by Tilden's PT 43, which was soon put hors-de-combat by a shell from the Japanese ship. As the enemy man-of-war closed with the 43, it peppered the sea around the stricken PT with machine gun fire as the crew expeditiously abandoned ship. The 43 continued running unmanned until she beached herself on the Japanese-held shore; out at sea, among the 43's crew, one man was killed and two men were missing.

As Tokitsukaze completed tormenting the crew of the 43, Japanese lookouts aboard the destroyer quickly spotted another torpedo boat running at high speed. It was PT 112; after passing astern of his would-be target, Larson turned the boat in an easterly direction towards Tulagi, trying to put some distance between his boat and the Japanese. Once more Tokitsukaze's gunners fired her main batteries, and two shells smacked the fleeing 112; one pierced the boat near the bow at the waterline, while the second scored a devastating hit near the forward bulkhead of the engine room, blasting an enormous hole in the hull, stopping the engines cold, and setting the compartment ablaze. Ed Guenther, on duty in the radio room, felt the shock of the two hits, and then heard the engines quit; upon hearing Westholm shout "Abandon ship", he quickly exited the radio room, scrambled up on deck, and jumped off the bow of the boat into the sea. Most of the crew had immediately abandoned the crippled PT, but in the burning engine room machinist's mate Clayton Craig, wounded by shrapnel, struggled with the CO2 release in an attempt to bring the fire under control; he finally succeeded, despite suffering burns on his face, arms, and hands. When the futility of trying to save the beat-up boat became apparent, the wounded machinist's mate and skipper Westholm were the last to abandon ship, joining the rest of the crew in the water. Most everyone seemed to be all right except for Craig and torpedoman Claude Dollar, wounded by shrapnel in one leg. As the shiprecked sailors began to take stock of their situation, they were startled by the sudden appearance of a Japanese destroyer that had turned on its searchlight. Cautiously scanning the area, the searchlight resting for a moment on the wrecked torpedo boat, then it began to make a sweep of the surrounding sea. Westholm and his men scattered, fearing the Japanese would massacre them with machine guns. After seeing the 112 dead in the water and apparently sinking by the stern, the destroyer snapped off its light and departed the area, leaving behind an utterly dazed and disoriented PT crew.

After the destroyer left, Bud Larson found himself alone in the darkness, burdened with his lifejacket, helmet, poncho, binoculars, pistol, and codebooks; the other members of the crew were in more or less a similar situation. The young ensign knew that other PT's would be out looking for them when they didn't report in at dawn, so he tried to make himself comfortable as possible and settled down for a long wait. Meanwhile Westholm, Guenther, and Craig had found 112's liferaft--a seven-by-three foot balsa oval--and after a period of time Larson bumped into them in the darkness. Later, the four sailors saw the 112, down by the stern with a five foot hole in her starboard side, but still afloat. Mr. Westholm considered reboarding it to retrieve a pair of binoculars that were a prized possession of his, and the four torpedo-boat men began to row towards the shattered PT. But once the raft got to within 100 feet of the 112, they promptly put that idea out of their minds when a small explosion in the smoldering engine room blew out the stern of the sinking boat. The sailors on the raft were picked up later that morning by a PT skippered by Lt. John Clagett, while four other 109 men were rescued by Lieutenant Amsden in PT 39; the remaining three sailors were fished from the sea by Stilly Taylor's PT 46. Save for Craig and Dollar, all hands were recovered uninjured. The PT 112 finally sank shortly after dawn on January 11th, one mile east of Cape Esperance; still later later that same morning, the crew of PT 115 spotted the 43 on the Japanese-held portion of the Guadalcanal shore; a New Zealand corvette was called upon to destroy the boat with gunfire to prevent its falling into Japanese hands.

After the battle, January 11, 1943. Above, radioman Ed Guenther (foreground) and Ens. Bryant Larson on the foredeck of a PT after spending the night adrift after PT 112 was destroyed. (Courtesy Ed Guenther) Below, the shattered hulk of PT 43. Photograph was taken after the Japanese had been run off Guadalcanal. (PT Boats, Inc.)

Four nights later, on January 14/15, thirteen PT's were out to meet the Express in a pitch-black night made worse by clouds and rain. The dirty weather made it almost impossible to see the bow of one's own boat, let alone find enemy warships. Westholm's 109 led Les Gamble's PT 45 and John Clagett in PT 37, and the three boats took their patrol station two miles southwest of Savo. Westholm later left Gamble and Clagett to make a search northwest of Savo, and had his only contact with the enemy when a floatplane swooped down and dropped three bombs; fortunately the bombs missed the PT by 150 yards. Early the next morning 109 was off the Guadalcanal coast, prowling the section of the shoreline the PT men called Machine Gun Row looking for enemy barges or supplies. Unknown to the 109's sailors, they were also under observation--by the crew of a hidden Japanese shore gun. The Imperial artillerymen held their fire until the PT cruised within range, then let fly with a few rounds, leaving three ugly holes in 109's hull. The PT gunners retaliated by strafing the underbrush with .50 caliber and 20mm fire. After this incident Westholm retired from the area, and headed back to base. Along the way the boat encountered Lieutenant Gamble's PT 45, beached on Florida Island following the PT-destroyer duel of the proceeding night. The 109 tried, but failed to pull the grounded 45 off the beach, and continued on to Tulagi. A Navy tug freed the high and dry PT later that day.

Changes were afoot for 109's crew; after their ordeal on the 112, January 18 saw the departure of some old faces, the arrival of some new ones, and the return of one former shipmate. The Navy had a "survivors leave" policy that sent any sailor who had survived a ship sinking home if he so chose. A few took advantage of the opportunity and went home, while some stayed in the combat area, working ashore with the Tulagi base force. Claude Dollar, Nicholas Mitrakos (who had replaced Joseph Morrisey as the cook in December), Ed Guenther, Clayton Craig, Adam Sennick, James Marney, and Lawrence Wallace all left the boat on January 18; XO Bryant Larson and quartermaster Guy Manning remained aboard. To replace the departing sailors, Lieutenant Westholm selected MoMM1/c Royal D. Dunkin, RM2/c George A. Lewis, SC2/c William S. Jackson, GM3/c Willam H. McMillan, S1/c James M. Bartlett, and TM2/c Jack Edgar, now 100 percent fit after breaking a leg in Panama. Two other sailors, F1/c Willam E. Griffin and F2/c Merrill D. Payton joined the crew a few days later. Jackson, McMillan, and "Ploughead" Lewis were former crew members of PT 110, and were riding PT 43 when that boat was lost on January 11. Dunkin, Bartlett, Payton, and Griffin were replacements from the base force. During this time, 109 was in drydock while her propellers could be serviced; in the meantime the new crew made two routine patrols on other boats; on January 22 aboard PT 115, and on January 26 aboard PT 110.

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2002-2013 by Gene Kirkland

|